Planetary Defense Crisis: NASA’s 2026 Blind Spot for City-Killers

Table of Contents

- The City-Killer Blind Spot: What We Can’t See

- The NEO Surveyor Saga: Delays and Consequences

- Budget Battles: The Efficiency Squeeze on Science

- The Deflection Gap: Post-DART Reality

- AI’s Role in Closing the Detection Gap

- The Artemis Paradox: Reaching for the Moon, Ignoring the Shield

- International Policy and the Rubio Doctrine

- Data Analysis: Known Threats vs. Defense Capabilities

- Conclusion: The Fragile Window of 2026-2028

Planetary Defense is the only major natural disaster that humanity has the technology to prevent, yet as of February 2026, a chilling admission from NASA has exposed just how fragile our shield truly is. At the recent American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conference in Phoenix, planetary defense officials confirmed a statistic that has unsettled experts and the public alike: approximately 15,000 “city-killer” asteroids—objects larger than 140 meters—remain completely undetected. While the world celebrates the return to the Moon, the systemic gaps in our ability to spot and stop these mid-sized threats have created a precarious window of vulnerability that will last until at least 2028.

This revelation comes amidst a turbulent political and fiscal landscape, where the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has rigorously scrutinized federal science expenditures, nearly leading to the cancellation of vital sensor programs. The public concern is no longer just about the science fiction scenario of a planet-ending rock; it is about the very real, statistical probability of a Tunguska-level event slipping through our blind spots while we argue over budget line items.

The City-Killer Blind Spot: What We Can’t See

The term “city-killer” refers to Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) roughly 140 meters (460 feet) in diameter or larger. Unlike the extinction-level giants (1km+)—of which we have found nearly 98%—these mid-sized rocks are elusive. As of early 2026, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) estimates that we have cataloged only roughly 40% of this population. That leaves a staggering 60%—roughly 15,000 objects—roaming the inner solar system unaccounted for.

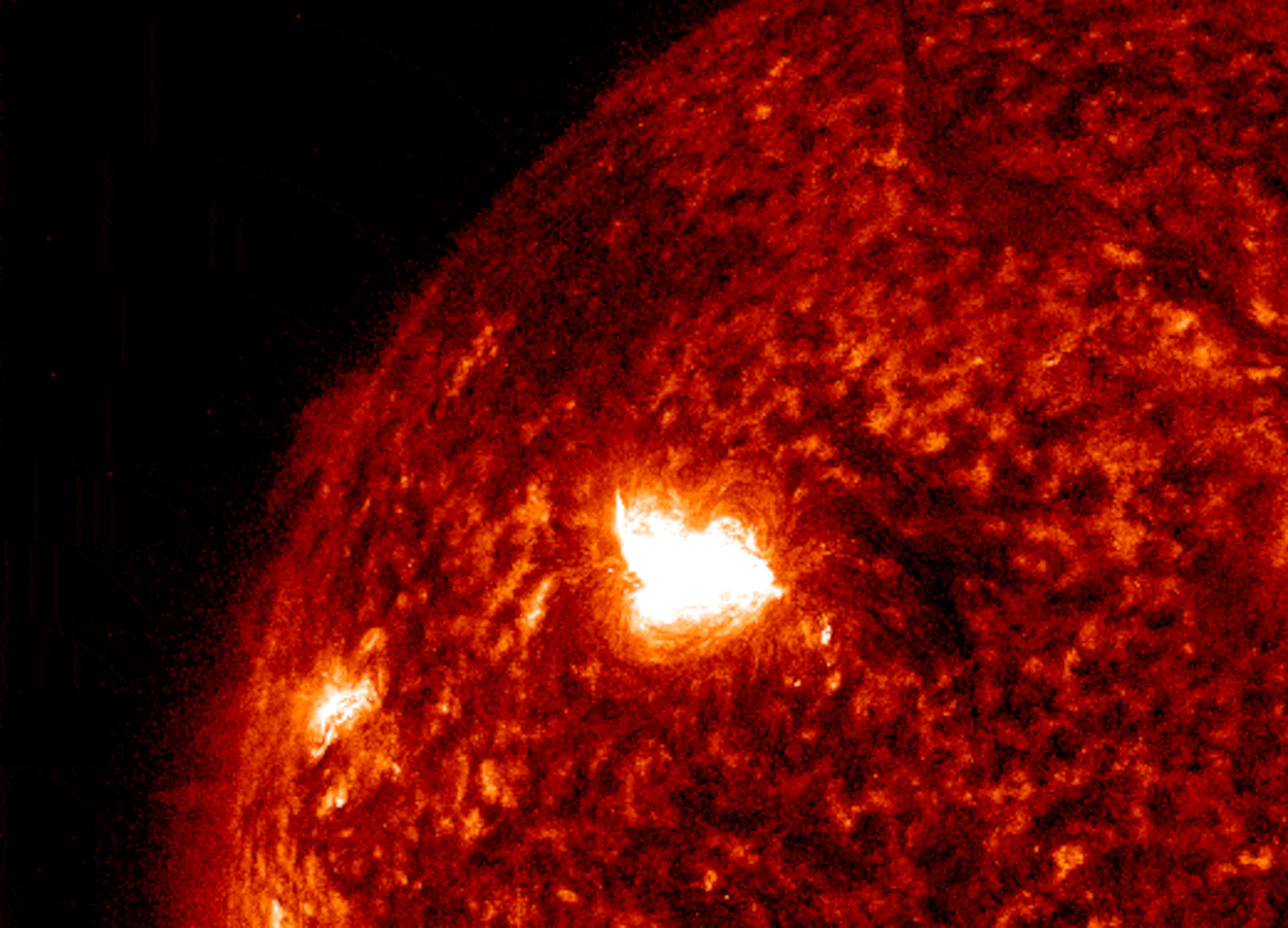

The primary technical limitation driving this blind spot is the sun. Ground-based telescopes, which form the backbone of current detection efforts (like Pan-STARRS and the Catalina Sky Survey), cannot look into the glare of the sun. Asteroids approaching Earth from the direction of the sun are effectively invisible until they are dangerously close. This was the exact trajectory of the Chelyabinsk meteor in 2013, which exploded over Russia with no warning. In 2026, despite thirteen years of technological advancement, this solar blind spot remains wide open.

Recent close approaches have exacerbated public anxiety. The flyby of asteroid 2024 YR4, which briefly carried a 3.2% impact probability for 2032 before being ruled out, highlighted the terror of “late detection.” Had that object been on a collision course, our current lead time would have been insufficient for a deflection mission. The public realization that we are effectively playing cosmic roulette with mid-sized impactors has shifted planetary defense from a niche scientific topic to a mainstream political issue.

The NEO Surveyor Saga: Delays and Consequences

The solution to the solar blind spot has existed on paper for years: the NEO Surveyor, a space-based infrared telescope designed to park at the L1 Lagrange point and look specifically for these dark, elusive rocks. However, the program has been a victim of chronic scheduling slides and budgetary brinksmanship. Originally targeted for a 2026 launch, the mission timeline has slipped to late 2027 or 2028.

This delay is not merely a logistical inconvenience; it extends the window of high risk. Every year the Surveyor is delayed is another year where thousands of city-killers pass through our neighborhood unmonitored. The infrared capability of the Surveyor is critical because it detects the heat signature of asteroids, making them stand out against the cold backdrop of space regardless of how much light they reflect. Without it, we are relying on optical telescopes that require the asteroid to reflect sunlight—a method that fails completely for dark, carbon-rich asteroids or those approaching from the day side.

Budget Battles: The Efficiency Squeeze on Science

The delay in planetary defense assets is inextricably linked to the broader fiscal environment of 2026. The aggressive auditing measures led by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) in 2025 proposed a historic 25% reduction in NASA’s overall budget, with the Science Mission Directorate facing a near-fatal 47% cut.

While Congress ultimately intervened in January 2026 to restore the bulk of this funding—securing $300 million specifically for NEO Surveyor—the uncertainty halted momentum. Program managers were forced to pause contracting, delay hardware acquisition, and bleed talent to the private sector. The “efficiency” narrative argued that ground-based observatories should suffice, ignoring the physics-based limitations of atmospheric interference and solar glare. This period of instability has likely cost the program an additional 12 to 18 months of readiness, a delay that critics argue pays for short-term savings with long-term existential risk.

The Deflection Gap: Post-DART Reality

While detection is half the battle, deflection is the other. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission in 2022 was a resounding scientific success, proving that a kinetic impactor could alter the orbit of an asteroid (Dimorphos). However, a successful test is not an operational defense system. In 2026, we have no “interceptor” rockets sitting on launchpads.

If a city-killer were detected today with a trajectory impacting Earth in six months, we would have zero capability to stop it. Building a duplicate DART spacecraft, integrating it with a launch vehicle, and calculating the intercept solution takes years, not months. The systemic gap here is the lack of a “Rapid Response” capability—a standby planetary defense mission class that can be deployed on short notice.

The European Space Agency’s Hera mission, launched in 2024, is currently en route to the Didymos system and is expected to arrive in late 2026. Hera will provide crucial data on the long-term effects of the DART impact, specifically regarding the “beta factor” (momentum enhancement from ejecta). Until Hera sends back this data, our understanding of how to scale kinetic impactors for larger or denser asteroids remains theoretical. We know we *can* move a rock, but we don’t yet know how *precisely* we can control the outcome for different asteroid compositions.

AI’s Role in Closing the Detection Gap

With hardware delays plaguing the physical sensors, NASA and private partners have turned to software solutions to bridge the gap. The integration of advanced Artificial Intelligence into astronomical data processing has become a critical stopgap measure. As detailed in recent analyses of agentic AI workflows, new algorithms are being deployed to scour archival data from the last decade.

These AI agents are capable of spotting faint moving objects in older images that human eyes and previous software generations missed. This “digital mining” of the sky has already identified hundreds of previously unknown NEOs in 2025 and 2026. However, AI cannot invent data; if an asteroid never reflected enough light to be captured by a telescope’s sensor due to geometry or distance, no amount of algorithmic brilliance can reveal it. AI improves the efficiency of our current eyes, but it cannot open the eye that is currently squeezed shut by the sun.

The Artemis Paradox: Reaching for the Moon, Ignoring the Shield

There is a palpable irony in the space community’s focus for 2026. All eyes are on the impending launch of Artemis II, the mission that will return humans to lunar orbit. As the final countdown for the Artemis II mission captures global headlines, planetary defense advocates point out the disparity in resources. The Artemis program commands a budget tens of billions of dollars larger than the Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

Critics argue that while exploration is vital for the human spirit and long-term survival, protection is a prerequisite for existence. The infrastructure being built for the Moon—heavy-lift rockets like the SLS and Starship—could theoretically be used for planetary defense, specifically for lofting heavy kinetic impactors or nuclear deflection devices. However, there is currently no formal “mission kit” or payload developed to utilize these vehicles for interception. The fear is that we are building the ship to sail the stars while ignoring the leaks in the hull of our own ship.

International Policy and the Rubio Doctrine

Planetary defense is inherently global; an impactor does not respect borders. The geopolitical landscape of 2026, shaped significantly by the new administration’s foreign policy, complicates international coordination. With Marco Rubio as Secretary of State, the U.S. has taken a more transactional approach to international treaties.

This shift has raised questions about the United Nations-mandated Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG). If a threat were detected, would the U.S. act unilaterally, or would it rely on a sluggish international consensus? The “Rubio Doctrine” emphasizes American aerospace dominance, which might suggest a willingness to lead a deflection mission, but it also casts doubt on data-sharing agreements with rivals like China, who are developing their own planetary defense capabilities. A fragmented response to a global threat remains a significant systemic risk.

Data Analysis: Known Threats vs. Defense Capabilities

To visualize the current state of vulnerability, the following table breaks down the threat classes and our 2026 readiness levels.

| Asteroid Size Class | Est. Population | % Discovered (2026) | Potential Damage | Current Defense Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planet-Killer (>1km) | ~900 | >95% | Global Extinction | High (Detection) / Low (Deflection Hardware) |

| City-Killer (140m – 1km) | ~25,000 | ~40% | Regional/Continental Devastation | Critical Gap (High Risk of Late Detection) |

| Town-Killer (50m – 140m) | Hundreds of Thousands | <10% | City Destruction (e.g., Tunguska) | Zero (Likely No Warning) |

| Airburst (<50m) | Millions | <1% | Windows Shattered/Injuries (Chelyabinsk) | Civil Defense / Evacuation Only |

Conclusion: The Fragile Window of 2026-2028

Public concern over NASA’s limitations is not born of hysteria, but of a rational assessment of the data. We are currently navigating a dangerous intersection of budget austerity, technological delays, and orbital mechanics. The gap between the proven science of DART and the operational reality of NEO Surveyor is measured in years—years where the Earth drifts unprotected against the 60% of city-killers we have yet to find.

The year 2026 serves as a wake-up call. The technology to secure our future exists; it is sitting in clean rooms awaiting funding and on hard drives awaiting analysis. As we look toward the arrival of the Hera mission and the eventual launch of the Surveyor, the question is not whether we can save ourselves, but whether we will choose to build the shield before the arrow flies. Until the Planetary Defense Coordination Office is fully funded and the infrared eyes of Surveyor open, we remain a planet crossing a busy highway with one eye closed.