Tyrannosaurus rex Predatory Behavior Revealed in Montana Fossils

Table of Contents

- Unearthing the Tyrant King in Hell Creek

- The Dueling Dinosaurs: A Snapshot of Prehistoric Combat

- Decoding Paleopathology and Ancient Disease

- Evidence of Intraspecific Aggression

- Biomechanics of the Bone-Crushing Bite

- Technological Revolution in Vertebrate Paleontology

- The Late Cretaceous Environment of Montana

- Conclusion: Redefining the Apex Predator

Tyrannosaurus rex remains the undisputed monarch of the Late Cretaceous, capturing the human imagination like no other prehistoric entity. Recent excavations and analyses emerging from Montana, particularly within the fossil-rich Hell Creek Formation, have fundamentally shifted our understanding of this apex predator’s behavior. For decades, the debate between scavenger and predator oscillated within the scientific community, but fresh evidence from 2025 and early 2026 has provided unprecedented clarity. By examining healed bite marks, stress fractures, and rare preserved interactions, paleontologists are painting a complex portrait of an animal that was not only an opportunistic feeder but a calculated, active hunter capable of engaging in violent intraspecific combat.

Unearthing the Tyrant King in Hell Creek

The Hell Creek Formation of Montana serves as the premier stage for these revelations. Spanning portions of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, this geological formation preserves the final moments of the Mesozoic Era. It is here that the density of Tyrannosaurus rex specimens is highest, offering a unique population sample size that allows researchers to study more than just anatomy; they can study ecology.

Recent field seasons have yielded specimens that challenge the solitary hunter hypothesis. The discovery of closely associated individuals suggests the possibility of gregarious behavior, or at least tolerance, among adults. While the concept of “pack hunting” remains contentious, the spatial distribution of these new Montana fossils implies that these massive theropods may have coordinated their movements to corral elusive prey like Edmontosaurus or the formidable Triceratops. The sedimentology of the region indicates a lush, subtropical delta environment, teeming with life yet prone to catastrophic flooding—events that fortunately preserved these giants in stunning detail.

The Dueling Dinosaurs: A Snapshot of Prehistoric Combat

Perhaps the most significant contribution to understanding Tyrannosaurus rex predatory behavior comes from the detailed analysis of the so-called “Dueling Dinosaurs” specimen. This fossil block, containing a tyrannosaurid (often debated as a juvenile T. rex or separate genus Nanotyrannus) and a ceratopsian preserved together, offers a frozen moment of prehistoric violence. Advanced preparation of this specimen has revealed teeth embedded in bone and reactive bone growth, confirming that these interactions were fatal encounters rather than post-mortem scavenging.

The position of the fossils suggests a dynamic struggle, with the predator maneuvering to avoid the lethal horns of the ceratopsian. This aligns with modern theories of theropod agility. Despite their immense bulk, T. rex possessed a specialized metatarsus (the arctometatarsalian condition) that enhanced stability and energy efficiency during locomotion. This adaptation would have been crucial in the uneven terrain of Late Cretaceous Montana, allowing the predator to ambush or pursue prey with surprising bursts of speed.

Decoding Paleopathology and Ancient Disease

Paleopathology, the study of ancient diseases and injuries, has become a cornerstone of reconstructing dinosaur behavior. By analyzing the scars left on bones, scientists can deduce the lifestyle risks of a Tyrannosaurus rex. Many specimens found in Montana show signs of severe physical trauma, ranging from broken ribs to infected jaws.

One particularly fascinating area of study is the presence of bone infections and osteomyelitis. In some cases, these pathologies resemble conditions found in modern birds and reptiles. Interestingly, the medical technologies used to diagnose these ancient ailments are paralleling advancements in modern healthcare. Just as we see global initiatives focusing on complex disease treatment, such as the efforts highlighted during World Cancer Day 2026, paleontologists are applying similar diagnostic rigor to dinosaur fossils. Identifying osteosarcoma or gout in a T. rex not only humanizes these monsters but proves they survived for years with debilitating conditions, hinting at a robust immune system or perhaps social support.

Evidence of Intraspecific Aggression

The life of a Tyrannosaurus rex was violent, not just toward prey, but toward its own kind. The skull of the famous “Jane” specimen and other Montana finds exhibit bite marks that match the dental spacing of other tyrannosaurs. These are not fatal wounds but face-biting scars, likely resulting from dominance displays or territorial disputes. This behavior is seen in modern crocodilians, where face-biting establishes hierarchy without resulting in death.

Such evidence effectively dismantles the idea of T. rex as a mindless eating machine. Instead, it presents an animal with complex social behaviors, capable of non-lethal conflict resolution. The frequency of these pathologies in the Hell Creek assemblage suggests a high population density where encounters between individuals were common.

Biomechanics of the Bone-Crushing Bite

The predatory success of Tyrannosaurus rex relied heavily on its jaw mechanics. It possessed the strongest bite force of any terrestrial animal known, estimated to reach over 35,000 to 57,000 Newtons. This capability allowed it to engage in osteophagy (bone-eating), pulverizing skeletal material to access nutrient-rich marrow.

| Feature | Tyrannosaurus rex Data | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Bite Force | 35,000 – 57,000 Newtons | Capable of crushing bone; accessing marrow; fatal localized trauma. |

| Tooth Structure | Serrated, banana-shaped, reinforced roots | Designed to grip and crush rather than slice; withstands high lateral stress. |

| Binocular Vision | 55-degree overlap | Depth perception crucial for judging strikes on moving prey. |

| Olfactory Bulbs | Enlarged relative to brain size | Ability to detect carrion or prey from miles away. |

Fossils of Edmontosaurus vertebrae found in Montana frequently show healed injuries where spinal processes were sheared off by a tyrannosaur bite. The fact that these prey animals survived indicates that T. rex was indeed hunting live prey and occasionally failed. These “ones that got away” provide the most irrefutable proof of predatory intent. A scavenger does not inflict a healing wound on a carcass.

Technological Revolution in Vertebrate Paleontology

The analysis of these Montana fossils has been propelled by a technological renaissance. High-resolution CT scanning, finite element analysis (FEA), and 3D modeling are now standard tools. We are no longer limited to the surface of the bone. Scientists can peer inside the braincase to reconstruct neurological structures, determining visual acuity and hearing range.

This integration of high-performance computing mirrors trends in other high-tech sectors. For instance, the massive computational power discussed in reports like SpaceX acquiring xAI for orbital data centers illustrates the scale of processing power now available. In paleontology, similar, albeit terrestrial, supercomputing clusters are used to simulate the physics of a T. rex bite or the stress loads on its femur during a run. These simulations help differentiate between biological reality and physical impossibility, refining our view of the predator’s maximum speed and agility.

Furthermore, chemical analysis of fossilized enamel is revealing isotopic signatures that tell us about the animal’s migration patterns and diet. We now know that T. rex likely did not stay in one small territory but roamed vast distances across the Laramidia landmass, driven by seasonal changes and prey availability.

The Late Cretaceous Environment of Montana

To understand the predator, one must understand the arena. The Hell Creek Formation 66 million years ago was a very different place from the arid badlands of today. It was a coastal floodplain, rich in vegetation and humidity, bordering the Western Interior Seaway. Towering conifers, ferns, and flowering plants provided ample cover for ambush attacks.

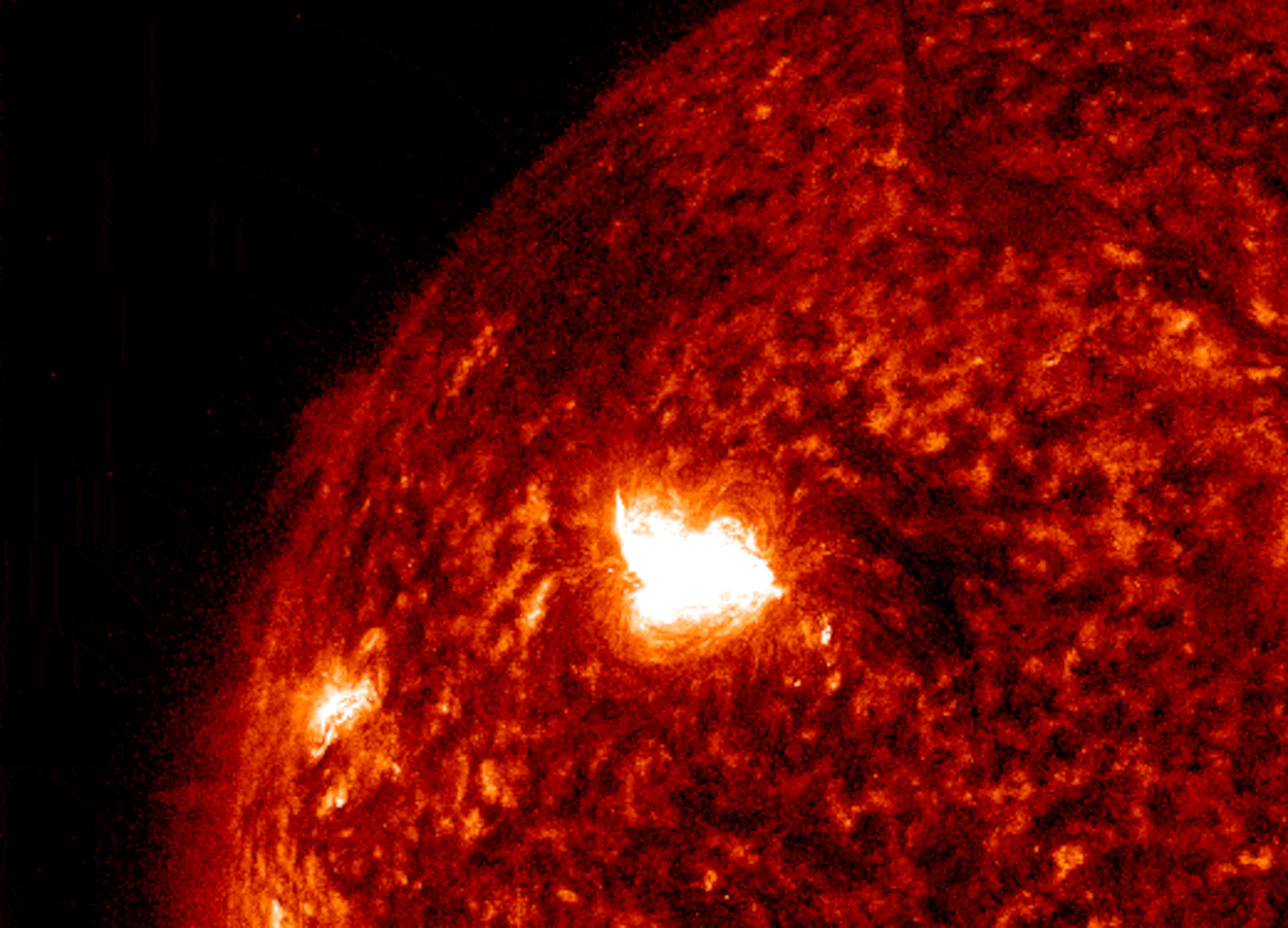

The environment was also subject to intense climatic fluctuations. Understanding these ancient climates often involves studying solar activity and atmospheric composition, not unlike modern studies tracking space weather events. While we monitor current phenomena like the historic X8.1 solar flares of Solar Cycle 25 to protect our technology, paleontologists look at the geological record for evidence of ancient environmental stressors that might have influenced dinosaur evolution and eventual extinction. The Late Cretaceous was a time of high volcanic activity and changing sea levels, creating a dynamic ecosystem where only the most adaptable predators could thrive.

In this lush yet volatile world, Tyrannosaurus rex was the keystone species. Its removal—or the survival of its prey—would send cascading effects through the food web. The fossil record shows a decline in diversity toward the very end of the Cretaceous, potentially making the ecosystem more vulnerable to the asteroid impact that would ultimately seal their fate.

Conclusion: Redefining the Apex Predator

The image of Tyrannosaurus rex has evolved from a tail-dragging sluggish lizard to a dynamic, intelligent, and socially complex bird-like predator. The fossils emerging from Montana continue to drive this transformation. Every broken tooth and healed rib tells a story of survival in a harsh world. While pop culture often lags behind science—a contrast often highlighted in entertainment critiques such as the future of indie cinema and storytelling at Sundance—the scientific reality of T. rex is far more terrifying and majestic than any movie monster.

As excavations in the Hell Creek Formation continue into the late 2020s, we can expect further revelations. Was T. rex covered in feathers? Did they care for their young for extended periods? The answers lie hidden in the sandstone of Montana, waiting for the brush of a patient paleontologist to reveal them. For more on the history of these discoveries, one can visit the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, which houses some of the most critical type specimens defining this genus.

In the end, the Tyrannosaurus rex was not just a killer; it was a biological masterpiece, perfectly honed by millions of years of evolution to rule its domain until the very sky fell.