Solar Cycle 25 Peak: Historic X8.1 Flare Threatens Global Grids in February 2026

Table of Contents

- The Historic Peak of February 2026

- Region 4366: The Monster Sunspot Analysis

- Infrastructure at Risk: Power Grids and Satellites

- Economic Fallout: Crypto Markets and Digital Assets

- The Science Behind the Storm: CMEs and Geomagnetism

- Comparative Analysis: Cycle 24 vs. Cycle 25

- Future Outlook: The Remainder of 2026

- Preparing for the Next Wave

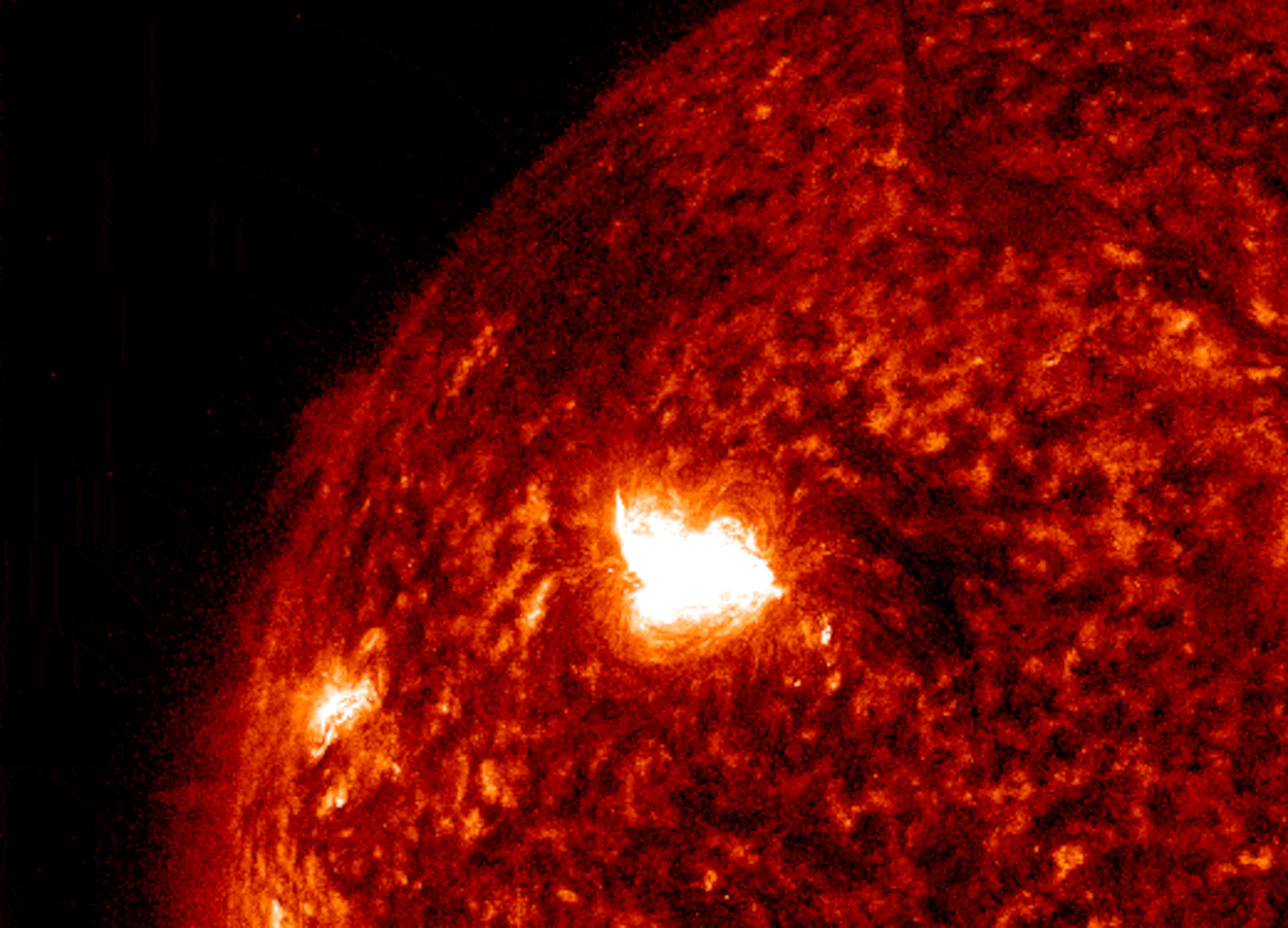

Solar Cycle 25 has officially entered its most volatile phase, marking a historic turning point in modern space weather history. On February 1, 2026, the sun unleashed a colossal X8.1 solar flare, the strongest eruption seen in over a decade, signaling that the solar maximum is not only here but is far more intense than initial models predicted. As Earth grapples with the immediate aftershocks of this geomagnetic assault, scientists and infrastructure planners are on high alert for what promises to be a turbulent spring. This comprehensive report analyzes the physics of the current peak, the specific threat posed by the active Region 4366, and the cascading impacts on global technology, from power grids to the digital economy.

The Historic Peak of February 2026

The trajectory of Solar Cycle 25 has defied nearly every conservative prediction made since its onset in 2019. Originally forecast to be a mild cycle similar to its predecessor, Cycle 24, the sun has instead produced activity levels comparable to the potent cycles of the late 20th century. The crescendo reached a new height in early February 2026, when a series of X-class flares bombarded Earth’s upper atmosphere, causing widespread radio blackouts across the Pacific and heightening anxiety regarding a potential "internet apocalypse."

The intensity of this peak is driven by the sun’s magnetic field flipping, a process that creates complex sunspot clusters capable of launching Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) directly toward our planet. The X8.1 flare recorded on February 1 was not an isolated event but part of a rapid-fire sequence that included X1.0, X2.8, and X1.6 flares within a 48-hour window. This density of high-energy events has saturated the near-Earth environment with charged particles, creating hazardous conditions for orbital assets and high-altitude aviation.

For a detailed breakdown of the specific event that triggered this global alert, read our in-depth coverage of the Solar Cycle 25 Peak: Monster Sunspot AR4366 Blasts Historic X8.1 Flare. Understanding the magnitude of this specific explosion is crucial for grasping the broader risks we face throughout the remainder of the year.

Region 4366: The Monster Sunspot Analysis

At the heart of this solar fury lies Active Region 4366 (AR4366), a sunspot cluster of such immense size that it is visible from Earth without a telescope (using proper eye protection). Spanning more than 200,000 kilometers across the solar surface, AR4366 possesses a ‘delta-class’ magnetic field, the most unstable configuration possible. This structure forces magnetic field lines of opposite polarity to press together, leading to explosive reconnection events that release energy equivalent to billions of atomic bombs.

Throughout the first two weeks of February 2026, AR4366 has remained a persistent threat. Even as it rotated towards the sun’s western limb, it continued to fire off high-energy particles. Space weather forecasters at NOAA have warned that as this region rotates back into view in late February, it may have destabilized further. The persistence of such a mega-region is reminiscent of the great storms of 2003, which caused power outages in Sweden and damaged transformers in South Africa.

The existence of AR4366 challenges our understanding of solar dynamo theory. The region’s rapid growth from a simple dipole to a complex, multi-core cluster in under 72 hours suggests that subsurface magnetic flux transport is far more dynamic than current models account for. This unpredictability makes it difficult for grid operators to prepare for the specific timing of impacts, forcing a reliance on real-time monitoring rather than long-range forecasting.

Infrastructure at Risk: Power Grids and Satellites

The primary concern during a peak of this magnitude is the vulnerability of Earth’s electrical infrastructure. When a CME strikes Earth’s magnetosphere, it induces Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs) in long conductors on the ground. These currents flow through high-voltage power lines, finding a path to ground through massive transformers. The result is often overheating, oil degradation, and in extreme cases, catastrophic failure of the transformer core.

In 2026, the grid is more interconnected and heavily loaded than ever before. The transition to renewable energy sources has introduced new complexities; while solar panels and wind turbines are generally resilient, the smart inverters and digital control systems that manage the flow of power are highly sensitive to voltage fluctuations. A GIC event could trip these digital safeguards, causing cascading blackouts similar to the 1989 Quebec event but on a potentially continental scale.

Furthermore, the threat extends beyond physical power lines to the digital backbone of our society. Just as physical infrastructure faces the risk of magnetic overload, our digital infrastructure faces threats from both natural and human-made vectors. The parallels between a solar-induced grid collapse and a sophisticated cyberattack are striking. For context on how supply chain vulnerabilities can be exploited in similar ways, see our report on Lotus Blossoms Infrastructure Hijack. Whether the disruption comes from a solar flare or a backdoor exploit, the result—mass incapacity of critical systems—remains the same.

Satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) are also facing a ‘density crisis.’ The influx of solar energy heats Earth’s thermosphere, causing it to expand. This expansion increases atmospheric drag on satellites, forcing operators to use precious fuel to maintain orbit. During the recent X8.1 flare event, several commercial satellite constellations reported orbital decay rates increasing by up to 50%, a sustainable rate that threatens to shorten the lifespan of billions of dollars of space hardware.

Economic Fallout: Crypto Markets and Digital Assets

The intersection of space weather and the digital economy is a growing field of risk analysis. Cryptocurrency mining operations, which rely on consistent power and internet connectivity, are particularly vulnerable to the disruptions caused by Solar Cycle 25. A sustained grid outage in a major mining hub could slash the global hash rate, causing transaction delays and spiking fees across blockchain networks.

Moreover, the high-frequency trading algorithms that dominate modern finance rely on GPS timing signals for synchronization. Solar flares can degrade these signals, introducing latency or errors that could trigger flash crashes in volatile markets. As we navigate the volatile first quarter of 2026, investors are closely watching how physical infrastructure resilience ties into digital asset valuation. For a deeper dive into the market outlook for this period, refer to our Crypto Prices Market Report Q1 2026 Outlook Analysis.

Global currency markets are also reacting to these technological risks. The fluctuation in fiat currency values often correlates with regional stability; a country whose power grid is deemed ‘solar-hardened’ may see its currency strengthen against nations with aging, vulnerable infrastructure. Understanding the technology behind global exchange is vital in this era of uncertainty, as detailed in our guide on Global Currency Exchange Technology and Science.

The Science Behind the Storm: CMEs and Geomagnetism

To understand why the X8.1 flare is so dangerous, one must look at the physics of Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). Unlike a solar flare, which is a flash of light and radiation that reaches Earth in 8 minutes, a CME is a massive cloud of magnetized plasma that travels slower, taking 15 to 72 hours to arrive. It is the impact of this plasma cloud against Earth’s magnetic shield that causes geomagnetic storms.

The severity of a storm is largely determined by the orientation of the CME’s magnetic field. If the field points southward—opposite to Earth’s northward-pointing magnetic field—the two fields link up, allowing solar energy to pour directly into our atmosphere. This process, known as magnetic reconnection, powers the intense auroral displays and the dangerous ground currents.

The X8.1 flare of February 2026 was associated with a fast-moving CME. While the bulk of the cloud delivered a glancing blow, the shockwave was sufficient to compress the magnetosphere to within geosynchronous orbit ranges. This exposure leaves satellites usually protected by the magnetic bubble exposed to raw solar wind, increasing the risk of ‘single event upsets’ where high-energy particles flip bits in computer memory, causing software crashes.

Comparative Analysis: Cycle 24 vs. Cycle 25

Comparing the current cycle to the previous one reveals a stark difference in intensity. Solar Cycle 24 (2008-2019) was historically weak, lulling grid operators into a false sense of security. Cycle 25 has already surpassed the peak sunspot numbers of Cycle 24 and is on track to rival the strong cycles of the 1980s and 1990s.

The following table illustrates the key differences between the peak of Cycle 24 and the current status of Cycle 25 as of February 2026:

| Metric | Solar Cycle 24 Peak (2014) | Solar Cycle 25 Status (Feb 2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Sunspot Number | 116 | 170+ (Estimated) |

| Strongest Flare | X9.3 (Sept 2017) | X8.1 (Feb 2026) |

| Geomagnetic Storms (G4/G5) | Rare | Frequent (Multiple in 2024-2026) |

| Grid Impact | Minimal | High Risk (Load stress, GPS issues) |

| Satellite Drag Events | Low | Severe (Starlink/LEO impacts) |

This data clearly indicates that the strategies developed during the quiescent 2010s are insufficient for the current environment. The frequency of X-class flares means that recovery time between storms is reduced, leading to cumulative stress on space and ground assets.

Future Outlook: The Remainder of 2026

Looking ahead, the forecast for the remainder of 2026 remains turbulent. The solar maximum is not a single point in time but a plateau that can last for two to three years. We expect high levels of activity to persist through 2027. The return of Region 4366 in late February and March poses an immediate threat, but new active regions are constantly emerging from the solar interior.

One specific area of interest is the high-latitude impact. As the auroral oval expands towards the equator during storms, regions that rarely see such activity are becoming prime viewing spots—and prime risk zones. The geomagnetic implications for northern territories are profound, affecting everything from local power generation to indigenous navigation. For a broader perspective on the geopolitical and ecological importance of these northern frontiers, consider reading about Greenland: The Arctic Frontier of Geopolitics and Ecology.

Scientists are also monitoring for "superflares"—events far larger than the X8.1, potentially reaching X20 or higher. Such an event would be comparable to the Carrington Event and could cause trillions of dollars in damage. While the probability of such an event is low, it is non-zero, and the current activity levels elevate that risk significantly.

Preparing for the Next Wave

As Solar Cycle 25 continues its rampaging peak, the message for governments and industries is clear: resilience is not optional. Upgrading transformer grounding, hardening satellite electronics, and diversifying timing sources for critical financial infrastructure are urgent priorities. For the individual, this means having backup power solutions and staying informed through reliable space weather alerts.

The sun is the engine of our solar system, and while it sustains life, it also dictates the terms of our technological survival. February 2026 will likely be remembered as the month the sun woke up from its slumber, reminding a digital civilization of its celestial vulnerability. For real-time updates on space weather conditions, you can visit the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center.